Sierra Leone's Silent Sage

FREETOWN—Chris During is no longer heard on the Sierra Leone Broadcasting Service. Silenced by politicians of past regimes, he tries to content himself writing, playing an occasional concert, and managing the dilapidated SLBS canteen. There he fishes soft drinks and beer from an old oil drum behind the bar and regales a succession of friends and visitors with stories of Sierra Leone’s golden age of entertainment—the three decades of prosperity immediately following World War II that fostered the flowering of the country’s modern music and theater.

During was born in Ghana, in the midst of the great worldwide depression of the 1920s and 1930s, where his Sierra Leonean parents had gone in search of prosperity. He grew up speaking Fanti and Ga and Ghanaian pidgin until, at the age of eight in 1934, he was sent to Freetown to attend school and soak up his Krio culture.

In Freetown he attracted a number of mentors. The Reverend Hycy Wilson of C.M.S. Grammar School, a pioneer in researching Krio language and culture, triggered During’s own enthusiasm for the subject. A teacher and playwright named Emerick Barnes encouraged his forays into acting and introduced him to entertainers like comedian Teddy Wilkinson and musician Ralph Wright. During apprenticed with Wright playing clarinet in his Blue Rhythm Band in the late forties.

After secondary school During joined the building trades then moved on to the post office where he put his bookkeeping and typing skills to work. But he says, “After a year or two I didn’t like it. I couldn’t see myself being a clerk, a pen pusher, an accountant all my life.” All along he had participated in children’s programs and variety shows on the Freetown re-diffusion service, a radio system begun in 1934 that transmitted programs by wire to receivers in people’s homes. “When the wireless broadcasting was inaugurated in l955,...I decided to switch over to full time entertainment,” he says. “And so I was fortunate to be one of the first generation of professional broadcasters in Sierra Leone.”

During was in his element at SLBS. In 1956 he created the Rokel River Boys, a radio show that combined music with During’s satirical, often biting, narratives about events in Freetown. The music was provided by a typical Krio maringa band—mandolin, guitar, flute, tambourine, and During on harmonica—which played traditional songs selected to complement the narratives.

Responsibility for the various SLBS band shows also fell on During’s willing shoulders. “In those days,” he recalls, “we were very few, and one man had to do many things. And seeing that I was musical...I produced all programs that had to do with bands.” That position thrust him squarely in the middle of Sierra Leone’s burgeoning recording industry.

Record shops had sprung up around Freetown selling the latest imports from Europe and America along with a wide selection from Africa on labels like Decca, Senafone, and H.M.V. In addition, several dealers started their own labels to record local musicians. Jonathan Adenuga, recording with a small Uher recorder and two microphones launched his Nugatone label. The Bahsoon brothers started Bassophone; A-Z, and later J.T. Stores, also began pressing records.

Because they had the best equipment, the SLBS studios were often used for recording sessions with During or his colleague Johnny Brown engineering. Recording was done in studio one, a large rectangular room with high ceiling. The musicians would be separated by movable wooden baffles so the sound each produced could be isolated from the others as much as possible. Each musician played through his own separate microphone which was connected to a control board. During would balance the instruments and singers at the board, blending them to achieve the desired sound. The master tapes would then be sent off to England for pressing into records.

During engineered S.E. Rogers's classic, “My Lovely Elizabeth,” and among scores of others, several songs by the Heartbeats, Super Combo, Salia Koroma, Big Fayia and Ebenezer Calender. He also put together a session band called The Invisible Five featuring prolific composer and guitarist Stanley Kabia to back singers who didn’t have a band.

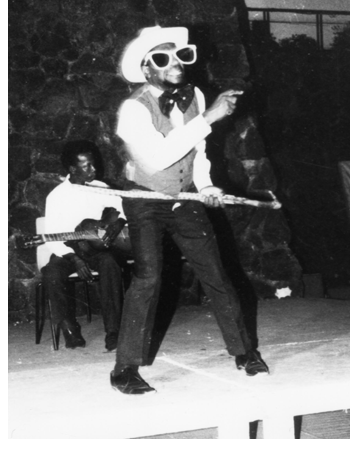

In 1964 During started his own dance band to play weddings and parties. The Versatile Publicans, as he called them, were an eight-piece band with During on vocals, clarinet, and harmonica backed by varying combinations of guitars, bass, drums, trumpet, trombone, and sax. They were versatile, he says, “because we don’t just play one type of music. We play all types of music, marches, religious songs, wake songs, dance music, weddings, Latin American, jazz.” The group played regularly until 1986 when equipment problems, the scourge of Africa’s musicians, forced them out of action.

Around 1966, in the later stages of Albert Margai’s regime, During began to have problems with the government over the content of his Rokel River Boys radio program. Much of the satire, it seemed, was hitting too close to home. He was finally banned from the airwaves in 1967, 1968, and 1969, the period of military intervention and transition to APC rule.

In 1973 he revived the Rokel River Boys idea, but this time instead of narratives he used drama to air his satirical commentaries. Maringa songs supported During and a cast of characters acting out situations relevant to the times. He called the program “Kris Na Kes,” literally Chris is a case.

It wasn’t long before he began to irritate the authorities once again. “All along, all throughout, every time, I would run into trouble with the politicians,” he says, his exasperation barely contained. “I ran into trouble with the SLPP. I ran into trouble with the military regime. I ran into trouble with the APC too.” By 1977, the government of Siaka Stevens had had enough. During was banned from broadcasting, a ban that is still in effect.

He has spent a dozen years of exile separated from his profession by the thin wall of the SLBS canteen. He sees his colleagues as they drop by to unwind and chat quietly about what painful, new indignity has befallen their once proud and vigorous station. He writes occasionally; he has authored two books, Kapu Sens, No Kapu Wod and its companion translation Krio Adages and Fables for the People’s Education Association of Sierra Leone. He assists a steady stream of researchers who have discovered Sierra Leone’s wealth of contributions to African music and theater. And he continues to exercise his comic wit for private audiences, sharpening it for that elusive day he is allowed to return to the airwaves.

This article first appeared in West Africa, no. 3770, 20 November 1989. Copyright © 1989 by Gary Stewart