Review

E.T. Mensah: On The Record and Off

Highlife music is enjoying a renaissance. A popular style of African music for more than three decades, beginning in the 1930s, highlife was suddenly swept aside in the mid-60s by the explosion of Congo music and an avalanche of sounds from British and American pop groups. Now, with African music capturing an increasing share of the international market, highlife is being discovered by new generations both inside and outside the continent.

Philips West African Records has re-released several old highlife albums including ones by Nigerians Victor Uwaifo and the late Rex Lawson. Another Nigerian, Dr. Victor Olaiya “The Evil Genius of Highlife,” has a compilation of old hits out on Polydor. Strong new offerings continue to come from African Brothers of Ghana as well as A.B. Crentsil and Highlife Stars to mention only a few.

Highlife music evolved in the British colonies along the West African coast. The colonies were musical melting pots of traditional rhythms of the indigenous people, piano and hymn music of Christian missionaries, brass band and fife and drum music of military garrisons, and other sounds of Europe and the Americas arriving via radio and records. African musicians borrowed the most appealing elements of foreign styles and incorporated them into their own works. The relatively staid rags, waltzes, and foxtrots were transformed in an African milieu of polyrhythms and syncopated melodies into a lively, danceable style more nearly befitting the African cultural concept of music as a functional, participatory element of society.

During highlife’s heyday in the 1950s, Iain Lang of The Sunday Times from London observed, “In the highlife the dancing couples promenade side by side—or sometimes yards apart—in a kind of rippling shuffle, punctuated by swooping gyrations, genuflexions or any other rhythmical movement the dancer is inspired to improvise. Improvisation is everything.”

While highlife has roots all along the West African coast, the Gold Coast, now Ghana, is widely credited as its birthplace. Located on the Gulf of Guinea, it was a major port of call for seafarers who plied the Atlantic waters. Ancient castles where slaves were held for shipment still dot the coast in places like Elmina and Cape Coast. Along with its people, the country’s gold and cocoa were highly sought after by European traders.

With the advent of the world wars, Europe’s African colonies became staging areas for Allied troops and fertile recruiting grounds for the enlistment of Africans to help fight in Europe and the Far East. In the Gold Coast's capital, Accra, saloons like the Roger Club, European Club, and later the Bashoun and Metropole, sprang up featuring local dance bands playing a variety of music, especially highlife, to entertain both Africans and Europeans.

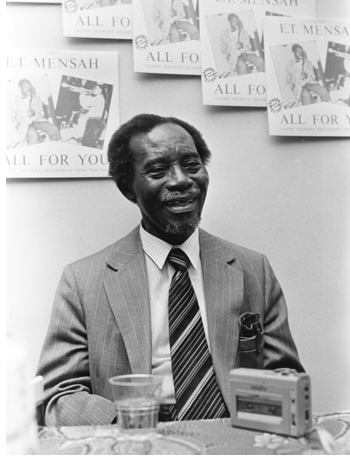

For many years the “king of highlife” was trumpeter, saxophonist, and band leader E.T. Mensah. Born in Accra in 1919, E.T. earned his title in the fifties and sixties when, together with his band the Tempos, he refined the dance band style of highlife and helped to spread its popularity beyond the borders of his own country. Now nearly 70, E.T. is gaining new recognition through the efforts of two Englishmen, Ronnie Graham and Graeme Ewens.

The two are partners in a new record company called RetroAfric which, says Graham, “was started to add some depth to the growing interest in African music.” The company’s first release is a compilation album of some of E.T. Mensah’s early recordings from the 1950s called All For You. Graham is also the owner of Off The Record Press, a new publishing house specializing in works on African music: “I started it over a year ago, retailing books on African music in an effort to raise money for publishing.” E.T. Mensah, King of Highlife by musicologist John Collins is the firm’s first publication.

Collins is an Englishman who has spent the majority of his life in Ghana; he grew up there and studied at the University of Ghana. As a musician he has played with many of West Africa’s leading bands, so he writes with knowledge gained through experience. With E.T. Mensah, King of Highlife, Collins tells the story of the man and the music he helped to create, largely through the words of the musicians involved. “The term highlife,” explains E.T.’s elder brother Yebuah, “was created by people who gathered around the dancing clubs....The people outside called it the highlife as they did not reach the class of the couples going inside, who not only had to pay a relatively high entrance fee of about 7s [shillings] 6d [pence]; but also had to wear full evening dress including top-hats if they could afford it.”

E.T. and Yebuah learned to read and play music under the tutelage of a teacher named Joe Lamptey. By the early thirties they had become proficient enough to be accepted into Lamptey’s legendary Accra Orchestra where they played a variety of woodwind instruments. From there E.T. moved on to play with several different bands, all the while balancing the demands of school work with those of his music. This schizophrenic existence continued into adulthood as E.T. qualified as a pharmacist and opened his own drug store while maintaining a stellar musical career.

The band which earned E.T. the greatest popularity was the Tempos. He assumed leadership of the group around 1938 and, despite numerous setbacks and changes in personnel, its popularity increased. Many of the Gold Coast’s best musicians served time in the Tempos including saxophonists Joe Kelly and Spike Anyankor, Guy Warren (now Kofi Ghanaba) the great drummer, and vocalist Dan Acquaye. As Collins explains, “E.T.’s role in the music scene in Ghana has been rather like that of Joe Lamptey; that of a teacher. Uncountable musicians have passed through his bands, and he has had a profound influence on dance band music in Ghana and in other parts of West Africa, particularly Nigeria.”

Collins’s approach to his subject is that of a scholar; he states what he is going to do and then does it. He quotes his sources extensively allowing them to relate the story as much as possible. The book’s organization is somewhat illogical as he chose to arrange the material around the occurrence of major events such as “Independence” and “Travels in West Africa” rather than taking a chronological approach. It is also a rather short book, 60 pages, and I found myself wanting to know more details. How did the recording sessions for Decca come about, where were they held, and how were the records produced? What were clubs like the Kit-Kat, Weekend in Havana, and E.T.'s own Paramount really like? Why did E.T. decide to pursue two careers instead of devoting full time to his music?

The book includes several wonderful old photographs as well as a discography. Unfortunately it also contains an inordinate number of typos and is victim of what appears to be a wayward computer program which leaves semi-colons and commas set apart from the words they should adorn like carriers of some literary contagion. The print is small and jammed together which is somewhat disconcerting as lines tend to get skipped or read twice. But enough of this discussion of technicalities; this is, after all, the first publication by an outfit that was “started with zero finance,” and the effort deserves praise. Certainly it sheds enormous light on the life and times of E.T. Mensah and the highlife music that he so heavily influenced. It is not a definitive biography by any means, but rather lays a foundation upon which others may build.

The album All For You is a result of Graham's affection for the music and resourcefulness as a record collector: “I have a large collection of 78s, all in pristine condition. I took them for remastering at Sound Archive, got the copyright from E.T. and then pressed 1,000 copies.” This gem of a record contains seventeen E.T. Mensah classics including some of the first recordings done with the Tempos in 1952. “Tea Samba,” featuring a fine guitar solo, and the title track are among those included from the band’s first recording sessions. More recording followed in 1953 and “St. Peter’s Calypso”—yes, the calypso craze swept Africa too—and “Donkey Calypso,” both with nice guitar solos to complement the horns, are products of those sessions.

Sweet sounding horns were E.T.’s trademark, and the horn section carries the load on each of the tracks. In fact, if it weren’t for the distinctive African rhythm section one could almost picture the band on stage at a night club in Harlem or Chicago or New Orleans in the 1930s. When Louis Armstrong visited the Gold Coast in 1956, he was greeted by an all-star band, including E.T., playing “All For You.” Iain Lang reported that Armstrong “immediately recognized this as the tune of a Creole song he used to hear in New Orleans half a century ago. Had it been brought to Accra, perhaps by a coloured seaman off an American freighter? Or had an old African melody survived both in the Gold Coast and on the Gulf Coast?”

The album’s one flaw is the lack of comprehensive liner notes. Particularly for a compilation as historic as this one is, it would be nice to know the recording dates and personnel involved. Liner notes by John Collins would have been a nice touch. This is a minor point, however, and will probably be of little concern to most record buyers. Purchase of the book as a supplement to the record is a simple solution for those, such as I, who crave details. These two offerings are wonderful additions to the growing body of work on the history of African popular music.

This article first appeared in The Beat, vol. VI, no. 1, 1987. Copyright © 1987 by Gary Stewart