The Music of Freetown

Maringa Roots, Rokoto Shoot

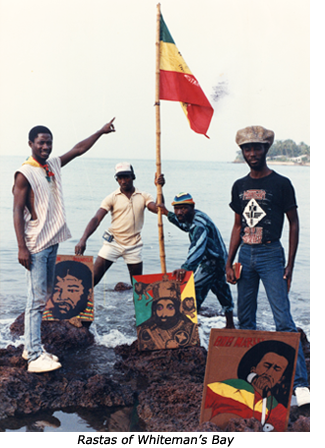

FREETOWN—Down at the foot of Macfoy Lane near the heart of the city, voracious tropical undergrowth reclaims crumbling foundations of old British military barracks, while a few yards away the waters of Whiteman’s Bay lap at the rocky shore. The beat of a loping bass and nyabinghi drums drifts from an unseen tape player in harmony with a warm onshore breeze. Seated nearby in the shade of a mango tree, a small group of Rastafarians passes the pipe and reasons together. Like their bredren in Montego Bay and Kingston, these sons and daughters of Africa, in Congo Town on the western edge of Freetown, Sierra Leone, seek relief from the slave mentality imposed by European colonialism and its homegrown successor. The meter and the message of reggae is big on these West African shores, where connections to the Caribbean abound.

FREETOWN—Down at the foot of Macfoy Lane near the heart of the city, voracious tropical undergrowth reclaims crumbling foundations of old British military barracks, while a few yards away the waters of Whiteman’s Bay lap at the rocky shore. The beat of a loping bass and nyabinghi drums drifts from an unseen tape player in harmony with a warm onshore breeze. Seated nearby in the shade of a mango tree, a small group of Rastafarians passes the pipe and reasons together. Like their bredren in Montego Bay and Kingston, these sons and daughters of Africa, in Congo Town on the western edge of Freetown, Sierra Leone, seek relief from the slave mentality imposed by European colonialism and its homegrown successor. The meter and the message of reggae is big on these West African shores, where connections to the Caribbean abound.

For centuries children of these lands had been herded onto slave ships anchored in Whiteman’s Bay and other inlets along the Sierra Leone River to begin the sickening voyage to sugar and tobacco plantations in the West Indies. As the abolitionist movement gained ground late in the eighteenth century, a new colony free from slavery but governed by the British was founded at Freetown. Many Africans who escaped from slavery in the Americas and many others recaptured by abolitionist forces from slavers on the high seas were settled in this new “province of freedom.” By the early 1850s, a missionary named Sigismund Koelle, who had gone to Freetown to teach Greek, Hebrew, and Arabic at the newly established Fourah Bay Institution (soon to become Fourah Bay College), had documented 160 languages and 40 dialects in Freetown—languages and people from Senegal down the coast and across the continent as far away as Malawi and Mozambique.

A new Creole culture and language, both called Krio, developed within this omnifarious mix. The language, largely English-based vocabulary with an African grammar, bears a strong similarity to Jamaican Creole. Jamaica also contributed its rebellious Maroon population to Sierra Leone at the end of the eighteenth century when many were deported by the British, first to Nova Scotia and then again to Freetown. Liberated Africans came from the other Caribbean islands and the United States as well, bringing with them traces of the old Africa and the New World.

Much of the colony’s music was generated by a plethora of self-help societies or companies (compin) which formed for the mutual benefit of the members. Some gathered for burial and wake keeping, others centered around marriage or birth. Tarancis societies were based on Temne ethnicity, although the Mandingo people later started their own versions. Hunters and carpenters and members of other vocations organized societies. African, Muslim, and Christian religious groups formed. Men’s societies and women’s societies, both secret and open, took their place alongside the others. Many had rites and rituals. Most had music. The largely percussion and vocal sounds of these societies melded with the music of West Indian regiments stationed in Freetown, the old folk songs and sea shanties of Kru sailors, and the hymns of Christian missionaries.

One of the most enduring styles to emerge from this mix is goombay (also gumbe). Goombay takes its name from the goombay drum, a square frame built like a stool with a skin stretched over the end where the seat would normally be. It is tipped on its side and the player sits on the frame while beating out the rhythm with his hands. Some scholars believe it originated in Nigeria and re-emerged among slaves in the Caribbean who then carried it back to Sierra Leone. To the goombay drum a typical ensemble adds a bass box, in the old days a large wooden box salvaged from shipments of kerosene tins or bottled beer; a carpenter’s saw, bent to produce the desired pitch and scraped with a wooden stick; and a triangle. The goombay drummer sings about well-known events, sometimes composing on the spot, while the other group members respond. It is still important, says Freetown musician and producer Chris During, because “up till today, a typical Krio wedding without goombay is no wedding....As soon as people begin to congregate the goombay will refuse to stop to play, because the more they play, people throw money at them.”

A more recent evolution of goombay is a street music called milo jazz. Milo (pronounced my-low) got its name from a popular brand of cocoa powder, because the empty tin was used like a drum as part of a group’s percussion array. But unlike the goombay ensembles, who follow set rhythmic patterns and whose cumbersome drum and bass box confine them to one place, milo groups are both improvisational and portable and are often seen parading around Freetown. A bugle or harmonica usually accompanies a milo band’s conglomeration of small drums, shakers, and triangle. Milo’s most famous practitioner, Olofemi Israel Cole, goes by the name Dr. Olo. Like the goombay musicians, Olo and the other milo bands sing stories about events in Sierra Leone.

Back in the eighteenth century, with its well-established colony and large natural harbor, Freetown became a major port of call for ships plying the West African coast. Increased commerce brought guitars, mandolins, accordions, and horns from Europe. In the early 1900s they were joined by gramophones and records and eventually radio. By the 1930s a modern music scene was developing everything from solo palm wine guitar, of which S.E. Rogie later became a great exponent, to swing dance bands like Ralph Wright’s Blue Rhythm Band.

From before World War II and on into the fifties another Caribbean connection also took hold in Freetown. Whether it arrived with the old West Indian regiments, as some have claimed, or on the new shellac 78 RPM records, as others say, calypso caught the fancy of many. Sierra Leone’s own calypso king was a singer named Ali Ganda. Sounding vaguely like Atilla the Hun, with the same New Orleans feel but a little more up-tempo, Ganda chronicled events in West Africa like “The Queen Visits Nigeria.” When in London on a study course he penned “Give Me Back Me Rice” in reaction to his new English diet. Unfortunately Ganda could often be found closing down the bar at Brookfields Hotel across from the Sierra Leone Broadcasting Service where he had risen to head of programming for television. He succumbed to the bottle in 1964 at the age of 37.

Another more authentically Sierra Leonean and largely Krio music evolved during this same wartime pre-independence period. It takes its name from the merengue of the Dominican Republic but sounds more like a blend of the calypso of Atilla the Hun and Ali Ganda and the palm wine guitar of S.E. Rogie’s predecessors. Called by its Krio pronunciation, maringa (sometimes spelled maringar), it serves the same function as calypso and goombay, telling about events as they happen. In fact there is such an affinity between the rhythmic patterns of maringa and goombay that players of each style often accompany each other.

Maringa groups usually include at least one guitar often supplemented by a banjo, mandolin, or second guitar; a wind instrument, most commonly tuba to play the bass line, plus trumpet or flute; and percussion pieces, small drums, bass box if there is no tuba, and triangle. Like the milo jazz groups, maringa bands are highly portable so the players can take to the streets.

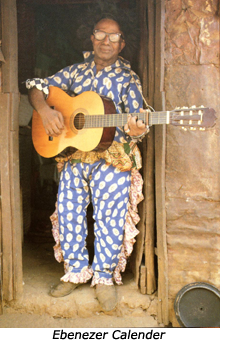

Freetown’s most famous maringa player was guitarist Ebenezer Calender, whose work and the era in which he lived are celebrated in a new compact disc from Original Music called African Elegant. Calender was the son of a Krio mother and a father from Barbados who had come to Freetown with one of the West Indian regiments. Calender played with a goombay group in the late thirties and taught himself guitar. Following World War II he began to record his songs in the small studio Decca had opened in Freetown’s east end. A prolific song writer, Calender also recorded for a number of small local entrepreneurs like the pioneering Jonathan Adenuga whose Nugatone label gave many Sierra Leoneans their first shot at making records.

Freetown’s most famous maringa player was guitarist Ebenezer Calender, whose work and the era in which he lived are celebrated in a new compact disc from Original Music called African Elegant. Calender was the son of a Krio mother and a father from Barbados who had come to Freetown with one of the West Indian regiments. Calender played with a goombay group in the late thirties and taught himself guitar. Following World War II he began to record his songs in the small studio Decca had opened in Freetown’s east end. A prolific song writer, Calender also recorded for a number of small local entrepreneurs like the pioneering Jonathan Adenuga whose Nugatone label gave many Sierra Leoneans their first shot at making records.

African Elegant presents fourteen Calender songs, re-mastered from old 78s, including three of his most famous, “Fire Fire Fire,” “Lumley,” and “Lilie Pepper and Lilie Salt.” Along with Calender the CD contains eight other selections from the same era, singer and banjo player Famous Scrubbs and two Tarancis societies among them.

Like the calypsonian, maringa players usually tell about events or humorous personal situations. One song puts Calender in the role of philandering husband advising his girlfriend to “Go Home and Come Tomorrow Night” because “the rain is coming now, and my wife is at home.” In another comment on family relations he teases, “You cook jollof rice, you no give me deh, you cook big foofoo, you no give you mother-in-law deh.” Scrubbs expresses surprise at seeing a “Woman Conductress” on the bus and sings about “equal work for equal pay” for Freetown’s women. The heyday of Freetown society resounds in this wonderfully odd and engaging collection. Put together with Original Music’s impeccable taste and attention to quality, African Elegant is mellow as a cup of palm wine, spicy as a ginger beer.

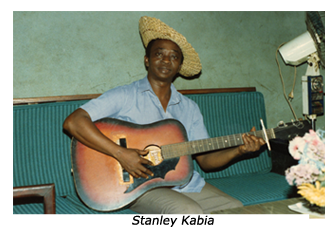

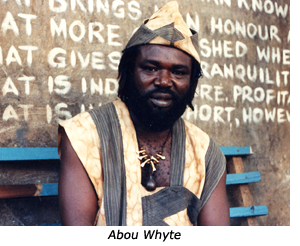

Following Calender’s death in 1985, another musician known as Dr. Loco has tried to carry on with a group he calls The Calender Survival Jazz. Goombay groups still place their stamp of authenticity on Krio weddings. Dr. Olo’s Milo Jazz band parties on. But the pop bands that elbowed Calender, Rogie, and their other elders aside in the rollicking sixties have all but died out. Sierra Leone’s recording industry, undermined by a declining economy and under attack from music pirates, collapsed in the late seventies. Most members of the two greatest bands, Super Combo Kings and Afro National, emigrated and play together no more. The Heartbeats, Ticklers, and Sabanoh 75 dissolved years ago. One of the country’s best composers, Stanley Kabia, writer of many of Afro National’s most memorable songs and guitarist with the Invissible (sic) Five studio band and a later group called Muyei Power, went back to the merchant marine. Singer Abou Whyte, another Muyei Power alumnus finds little work in today’s Freetown. The explosive Dr. Dynamite sells a less incendiary commodity, stationery. Big Fayia records occasionally in Côte d’Ivoire, but earns a living entertaining tourists with his troupe of traditional dancers. What little Sierra Leonean music that makes it onto compact disc or cassette these days comes, for the most part, from London.

Of the old-timers only the artful palm wine veteran, S.E. Rogie, has managed to find new life abroad. From the sixties, Soundcasters’ singer Bunny Mack and the Heartbeats’ Francis Fuster continue to record and perform in London. But grabbing the most attention, so far in the nineties, is a new generation of Sierra Leonean exiles for whom Freetown’s musical flowering is but a fond and distant memory from pre-adolescence.

Of the old-timers only the artful palm wine veteran, S.E. Rogie, has managed to find new life abroad. From the sixties, Soundcasters’ singer Bunny Mack and the Heartbeats’ Francis Fuster continue to record and perform in London. But grabbing the most attention, so far in the nineties, is a new generation of Sierra Leonean exiles for whom Freetown’s musical flowering is but a fond and distant memory from pre-adolescence.

Best known purveyor of Sierra Leone’s new London sound is guitarist Abdul Tee-Jay. Abdul Tejan-Jalloh was a young Freetown schoolboy in the days when Super Combo and Afro National battled for musical supremacy. He picked up guitar listening to these great bands and the Congo music recordings of Dr. Nico. In 1974 he left Freetown to study economics in the United States and wound up in London five years later. With academics more or less behind him, Tee-Jay and another of the new generation, Mwana Musa, put together a group called African Connexion which recorded a variety of songs but leaned toward crossover grooves like “Dancing on the Sidewalk.” Once divorced from African Connexion, Tee-Jay drifted toward more rootsy stuff like his B.A.D. production “Salima.”

Ten years after he arrived in London Tee-Jay found his musical path with a new band he named Rokoto, which means to dance in Krio, and a new album, Kanka Kuru. In a 1989 interview with Folk Roots magazine he explained that for his Rokoto sound he “started writing Sierra Leone songs using old folk songs and developing them. So that’s the base of it. I can’t ignore soukous, I can’t ignore highlife, but everything I play should be based on Sierra Leone music.”

Abdul Tee-Jay’s newest, just out on Rogue Records, is a nine-song sizzler called Fire Dombolo. It leads off with one of the best African tracks of the nineties, so far at least, a great instrumental billed as a “marriage of highlife, soukous, makossa and milo...with American jazz,” called “Rokoto Jazz.” This cut sets a high standard, but Rokoto manages to reach its level again on a couple of other tracks. “Ansu,” the story of an adolescent boy, “Salimatu,” a girl whose dowry (in Sierra Leone, money given by a prospective husband to the prospective bride’s parents) is too high, and a love song to “Sara Douala” all click nearly as well. Tee-Jay’s lyrics, although brief and often repeated, echo the story-telling character of Calender’s maringa. Musically Rokoto recalls the early eighties Paris productions of Richard Dick and Eddy Gustave along with snatches of Super Combo and Afro National—up-tempo yet not as frenetic and monotonous as the TGV soukous of Loketo and Matchatcha.

Like it or not, African music of the 1990s—at least that which reaches the west—will be largely the music of artists living outside the continent. Ebenezer Calender’s maringa captured the essence of 1950s Freetown. Consciously eclectic sounds like those of Rokoto and its Parisian counterparts more closely mirror first world melting pots and the struggle for an African identity in exile. Both are signposts on the road of Africa’s evolution.